CRANBROOK ACADEMY OF ART

Cowan Pottery became a victim of the Great Depression. In 1932 Gregory gained a position as artist-in-residence for ceramics at the Cranbrook Academy of Art in Bloomfield Hills, Michigan. Cranbrook was among the most prestigious places in America to study modern design during the 1930s. Among its faculty were architect Eliel Saarinen, designer Charles Eames, and sculptor Carl Milles.

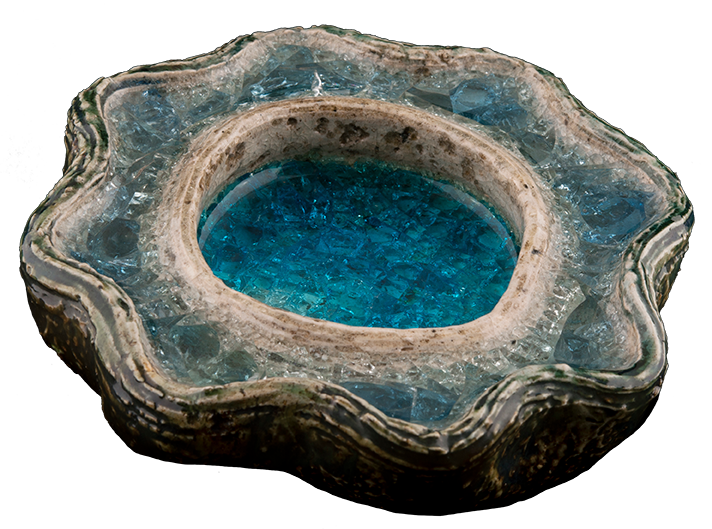

Gregory taught and worked at Cranbrook from 1932 to 1933. There he shifted his focus to studio ceramics rather than commercially produced art pottery, handling all aspects of the production of his work.

Credit

"SE Bloomfield MI RPPC Academy of Art Museum Grounds Cranbrook Private School Academy of Art Public Science Museum and Planetarium Photographer CROZE Unsent Card 4" by UpNorth Memories - Don Harrison is licensed with CC BY-NC-ND 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/2.0/